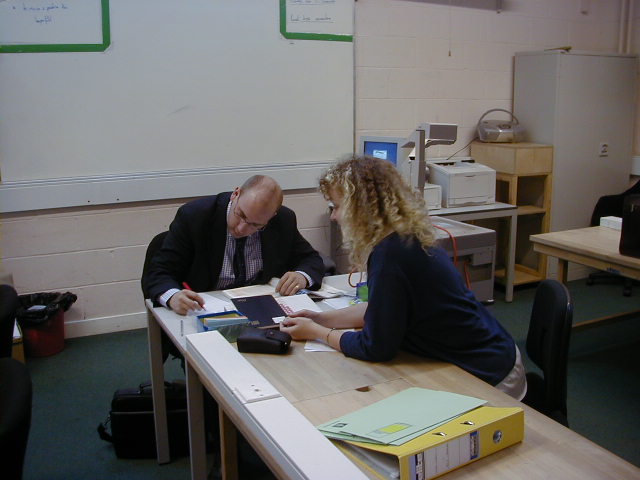

Photo: Nicole Brown

Being a mentor for a trainee teacher can definitely be one of the most rewarding tasks of a teacher. Every well-planned lesson that arouses pupils’ interests and stimulates their curiosity so that they finally leave the classroom having been challenged and having learnt something new, motivates not only the trainee teacher but also his/her mentor. All the formal mentoring sessions, the college assignments as well as the informal chats on the phone and in corridors suddenly come together and bear fruit. And although it is the trainee teacher’s achievement to have mastered the art of planning and delivering a successful lesson, the mentors, too, feel pride and reward.

However, being a mentor is also one of the most challenging tasks of a teacher. The main pressure is not, as is often stated, lack of time to fulfil the mentoring tasks to one’s best abilities, but in satisfying the trainee’s thirst for more information, without placing undue stress on them. In various publications it has been pointed out that trainee teachers suffer from stress, due to being assessed constantly and due to their heavy workload (Head, Hill & Maguire, 1996).

For school-based mentors, it could be easy to forget that the trainee teachers are not only confronted with planning and delivering lessons and have to cope with the sometimes frightening feeling of controlling classes of up to thirty pupils, but also have to fit in assignments set by colleges or training centres. Although these tasks help to meet the qualified teacher standards, trainee teachers often feel overburdened and can hardly understand the relevance of such assignments. In these cases, it is the school-based mentors’ duty to support the trainees with planning and structuring assignments, but more importantly to mediate between the training centres and the trainees.

Often, however, the tasks raise complex questions concerning teachers’ roles, responsibilities and philosophies, which the trainee teachers find difficult to answer, as they have not developed their own “teaching identity“. Finding their own values becomes even more complicated for the trainee teachers, because they feel the constant pressure of being assessed.

Therefore, mentoring sessions are often about offering new insights into an experienced teacher’s life, set of values and philosophy of teaching. Certainly, it is the trainee teachers’ ultimate decision which perspective to adopt, in reality, however, they are always conscious that the identity they develop will be judged, criticised and assessed.

Mentoring therefore is a balancing act between the requirements of colleges and training centres, the qualified teacher standards, the personality of trainee teachers and the constant fear of overwhelming trainees. Although the mentors’ standpoint is clearly not easy, the smiles on a trainee teacher’s face after successful lessons is definitely worth every battle against all odds.

Reference:

Head, Hill & Maguire. (1996). “Stress and the postgraduate secondary school trainee teacher: a British case study”. Journal of Education for Teaching.

Leave a message: